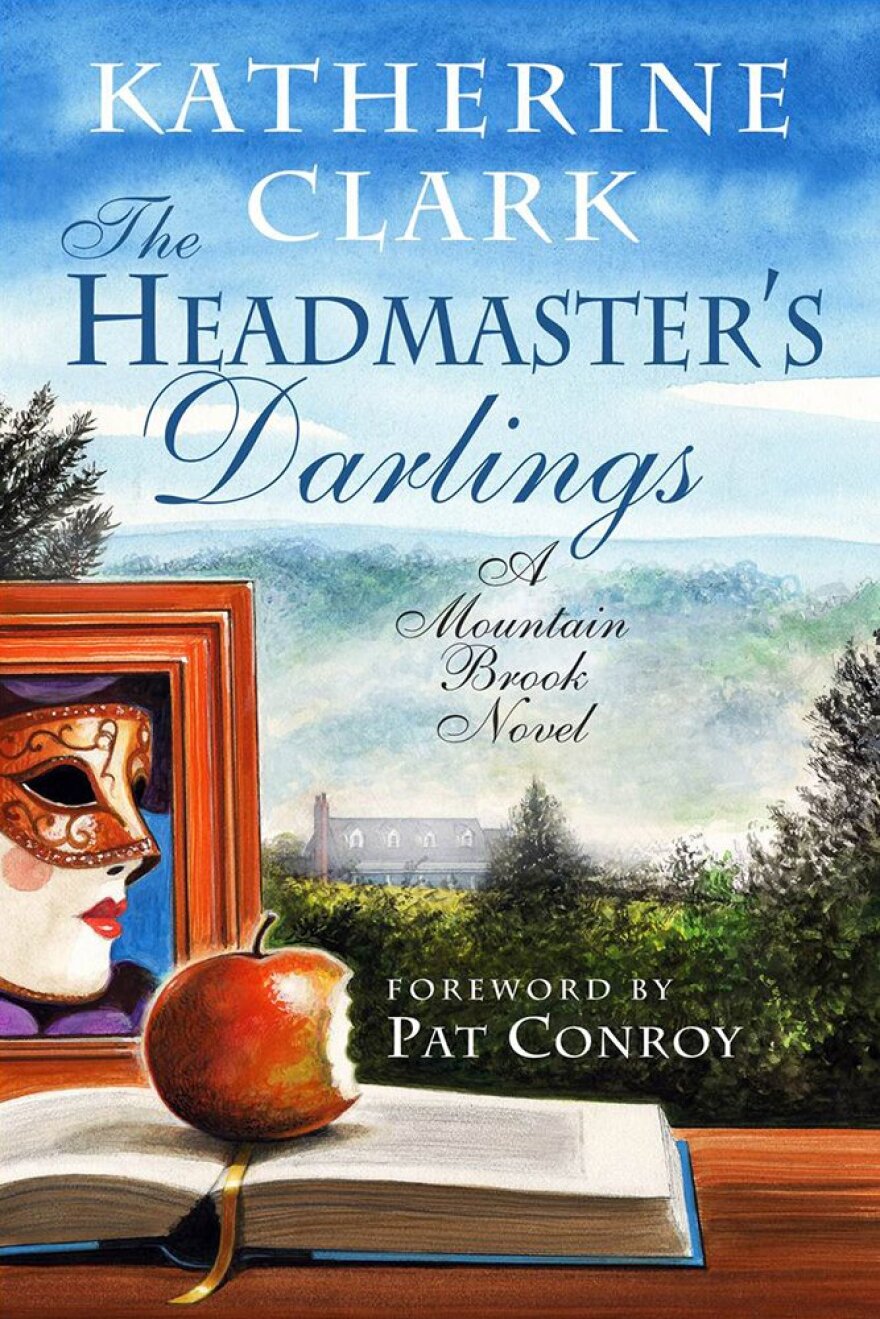

“The Headmaster’s Darlings: A Mountain Brook Novel”

Author: Katherine Clark, with a Foreword by Pat Conroy

Publisher: University of South Carolina Press: Story River Books

Pages: 248

Price: $29.95 (Hardcover)

Two fine Southern writers have teamed up on a couple of ambitious new projects, and the enterprise needs some explaining. Katherine Clark‘s first book was “Motherwit,”(1989) an as-told-to biography of midwife Onnie Lee Logan. Then Clark published “Milking the Moon,”(2001) Mobile writer Eugene Walter’s life story, again as-told- to.

These books attracted the admiration of Pat Conroy who has now told HIS life story to Clark, in face-to-face interviews and daily over the telephone, the volume to be published next year.

In the meantime, as if the author of “The Prince of Tides,” “The Great Santini” and nine others weren’t busy enough, Conroy has become the series editor of Story River Books, novels coming out of the University of South Carolina Press.

Clark has, most unusually, even unbelievably, written a quartet of novels set not in exotic Alexandria, as were Lawrence Durrell’s, but in Mountain Brook, Alabama. The first of these, “The Headmaster’s Darlings,” is just out and is first-rate.

Clark, a native of that enclave of privilege, attended the Altamont School, here called the Brook-Haven School (and later Harvard), and was clearly paying close attention.

In his Foreword, Conroy recalls teachers important to him, the men and women praised in Conroy’s “My Reading Life,” a remarkable memoir, and he says Clark’s protagonist may be even more impressive. Conroy also pays the highest compliment to a book of this sort—a comedy of manners that depends so heavily on the observed detail: “What she has done is create a world” in the way that Dickens created London for his readers or Saul Bellow created Chicago.

“The Headmaster’s Darlings” is set in 1983-84. The protagonist, Norman Laney, is modelled closely after Carl Martin Hames, the larger than life, in fact 600-pound, theatre director and teacher of English and art history. Hames’ photo even appears among the front matter. In the novel, Laney is Falstaffian, Gargantuan, huge, but, hiding in plain sight, he is a subversive force, an agent inside enemy lines.

Originally from blue collar Pratt City, Laney teaches in Mountain Brook but is not of it. He lives in one of the few apartment buildings in Mountain Brook, a building usually occupied only by “the newly-wed or nearly dead.”

Real people live in nice homes.

Extroverted, jolly, witty, extraordinarily bright and cultured, Laney believes most of the rich parents of his students to be “barbarians.” That is, their values are vulgar, shallow, crass, materialistic, conformist, barely “capable of redemption.” He can’t save these people, especially not the husbands: golfing, hunting, football-crazy lawyers and bankers. But he can save some of their children. He works with the students he identifies as special, convincing them to get away to Harvard, or Columbia or Vassar. Money is, after all, no object. He wants them to taste, to experience, the greater world. He wants them “to aspire to something. Not money or power, but something that would satisfy their soul’s yearning for fulfillment and transcendence.” Laney lights fires. He encourages young people “to aspire to the top.” Laney sees that it is not only poor kids who lack a grand vision. “Children from Mountain Brook also suffered from the low expectations of their society, which primarily demanded that the daddy be rich and the mama good-looking.” (The run-of-the-mill nice kid will join the Greek system in Tuscaloosa and then return to a life in Mountain Brook, values unchallenged and unchanged.)

Many parents would think this to be meddling. They don’t know the half of it. Laney can see what a youngster is struggling to be, and encourages this, even if it means coming out as gay or something really bold, like becoming an artist.

Surprisingly, he also urges these “escapees” to return afterwards, if they can, and then work to “civilize” their home place, even to go so far as joining the Junior League to make it the service organization it ought to be.

This all sounds serious, but “The Headmaster’s Darlings” is a comic novel, a satire in the eighteenth-century style, skewering both well-established snobs and the pretentious newly rich, poor souls who have enough money to live in Mountain Brook but will never get into the Country Club, try as they might. In their homes, the walls all have “lavishly framed prints of ducks and birds.” The bookshelves hold not books but “pricey knickknacks.” The ladies’ hair is too perfect, not a strand out of place and uniformly dyed. And on what Laney calls “the Junior League ring finger” are the diamond solitaire of the wedding ring “accompanied by so many stone-studded bands that her finger looked like it had been colonized by diamonds.”

Some, no matter how wealthy, won’t be accepted because, alas, they are “outsiders.” Laney muses: in the typical Mountain Brook mind, everyone not from here, even someone from Idaho, is a Yankee and all Yankees are Jews. Ipso facto, all those not from here are Yankee Jews, not socially acceptable.

While the men amass the money, their women, mostly separately, live pampered but nervous lives. For most “life as sought-after belles had been so much more fun than their lives as married women.” “Mountain Brook ladies had always struck him as being unacquainted with ecstasy of any kind.”

But those ladies love Laney, who pays them attention, flirts a little and listens to their woes. Secretly he disdains most as frightened conformists, but he has his favorites. Laney appreciates real style and character when he sees it: independent women who have realized that “Public opinion…was a weakling, and a coward which usually deferred to the force of a strong personality.”

Certain plot lines are set in motion in this novel which, remember, has at least three sequels. Unspecified charges of misconduct are brought against Laney. A mother of one of his students dies under inexplicable circumstances. These threads will be followed in the books to come.

One wonders how all this will go down with readers in Mountain Brook. On the one hand, after Thomas Wolfe wrote “Look Homeward , Angel,” Ashevilleans were furious and Wolfe famously wrote “You Can’t Go Home Again.” On the other hand, the objects of ridicule rarely recognize themselves. The figure being lampooned is someone else, in the house down the road.

We’ll see.

This review was originally broadcast on Alabama Public Radio. Don Noble is host of the Alabama Public Television literary interview show “Bookmark” and the editor of “A State of Laughter: Comic Fiction from Alabama.”