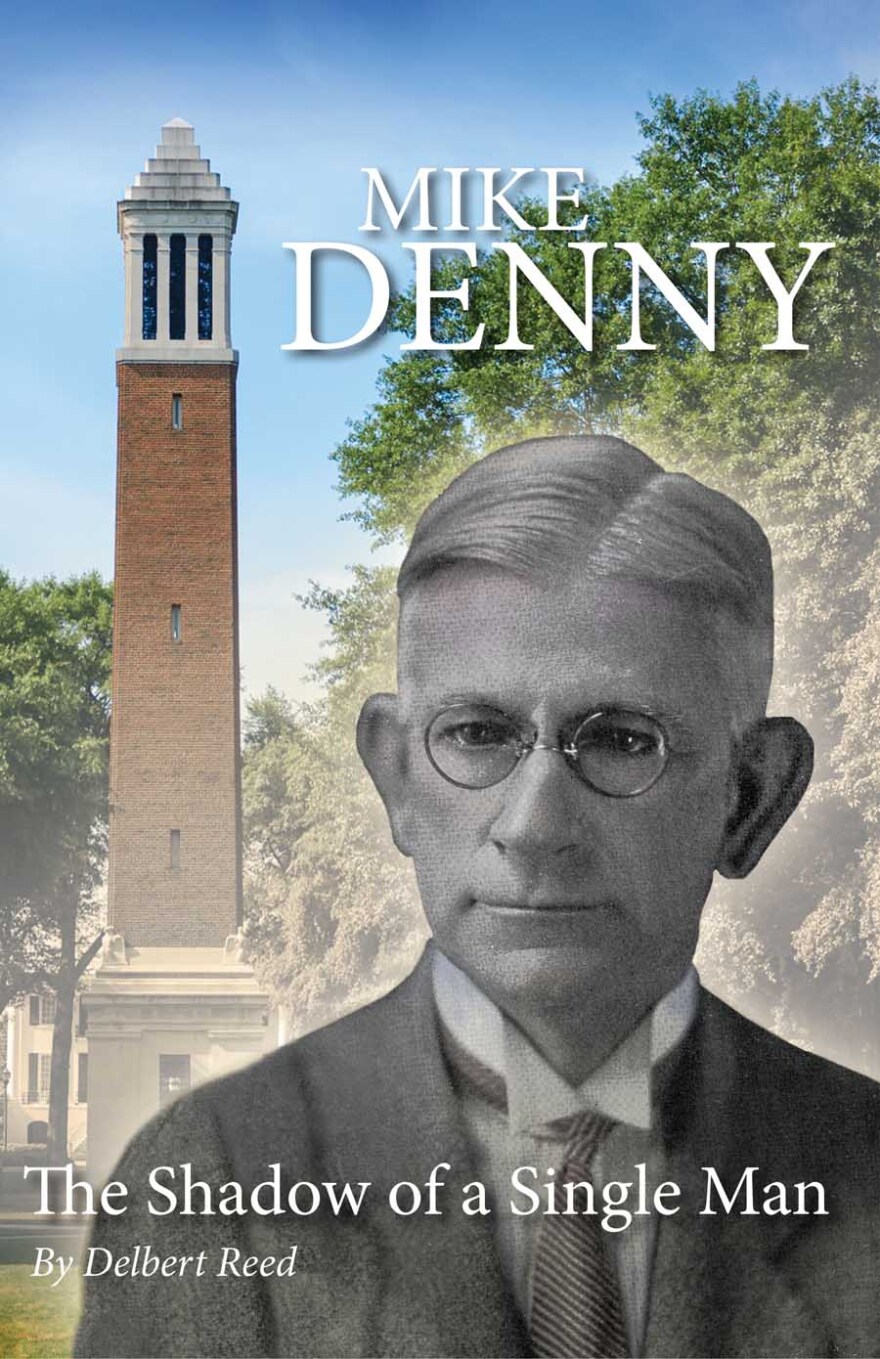

“Mike Denny: The Shadow of a Single Man”

Author: Delbert Reed

Publisher: Paul W. Bryant Museum

Pages: 325

Price: $24.95 (Hardcover)

Dr. George H. Denny, known to all as “Mike,” was an extraordinary man. Born in the town of Hanover Courthouse, Denny was a patriotic Virginian, steeped in the lore of the Commonwealth: Washington, Jefferson, Patrick Henry, Stonewall Jackson. After graduating first in his class at Hampden-Sydney College in 1891, he took an M.A. there and then a Ph.D. from U. Va. in 1896. After three years of teaching Latin and German at his alma mater, Denny joined the faculty of Washington and Lee as professor of Latin and was, to everyone’s surprise, made president in 1902, at age 31.

Robert E. Lee was, not surprisingly, Denny’s hero. Choosing duty and service over gain, after the Civil War Lee turned down lucrative job offers, instead choosing to lead at Washington University, where there were fewer than 50 students in 1865, and four faculty.

In 1901, W&L was again struggling with finances and low enrollment, with only 200 students. Denny took command and really turned it around. It is said he never took a day of vacation. After 10 years, there were 630 undergraduates, new buildings everywhere, and the finances were sound.

Educators everywhere noticed and Denny was offered the presidency of the University of Alabama in 1911.

This was an excruciating decision for the Virginian. Reed quotes excerpts from 14 letters to Denny. Most begged him to stay, but Denny believed he could accomplish more in Tuscaloosa, on a broader stage: “It seems clear to me that the great influence in the South is to come through the state universities....”

He saw The University as a public treasure which should serve the state but also be “the head of a statewide school system …. as a means of changing the economic, social and cultur[al] climate in Alabama and thus improving the lives of the citizens of what was then a poor, undeveloped, agrarian state ….” He was not just building the school; he was building the commonwealth.

In many ways he succeeded. Twenty-five years later, at his retirement in 1936, enrollment had risen from about 400 to about 5,000, four classroom buildings became 15, one fraternity house became 22, with 12 sororities where there had been one. He also communicated relentlessly with alumni and built the endowment, a priority of his.

Denny accomplished all this with little support from the rural-dominated legislature, which constantly short-changed the University in favor of Auburn. In 1918 Auburn received $117,280, with $71,000 for Alabama.

In 1935-36 Auburn received $153, Alabama $72 and, surprisingly, Alabama College (Montevallo) $268 per student, although UA had far more students than either, by far. Other state universities averaged $241 per student.

Alabama had the lowest per-student expenditure in America.

He grew famous for his parsimony. It was said he “squeezed the nickel until the buffalo cried.”

A famous micro-manager, Denny wrote to EVERY high school senior in the state urging them to enroll and he wrote to many in the summer urging them to return.

He arranged campus jobs for thousands.

Reed reports “Denny… reserved practically all lower-lever campus jobs for the students, including clerical, laundry, grounds-keeping, power plant firemen, library assistants, stenographers and typists, cafeteria waiters and janitorial staff positions.”

It was said Denny knew every student by name, and greeted them personally, whenever they crossed paths.

Crowding was fierce; some students lived on the first floor of the president’s mansion.

He also expanded summer school, the extension division, and most importantly recruited more women and more out-of-state students—1,806 in 1930. In 1932 more than half of the freshman class were out of state students. There were four Jewish fraternities, two Jewish sororities and one Italian fraternity.

Critics complained that Alabama money was paying to educate “foreigners.” Denny replied that the out-of-state tuition–a fee of $60.00 per semester, per student—was educating Alabamians.

Some things have changed; some have not.

It is disappointing that we get little sense of Denny the private man, husband and father, but the first 100 or so pages of Reed’s biography do summarize Denny’s public life rather well.

The next 200 pages, however, are mostly a giant collection of speeches, letters to and from Denny, resolutions of the board of trustees, and newspaper editorials, quoted at excessive length and with stupefying repetition.

For example, when Denny announced he was retiring in 1936, there was an outpouring. Reed quotes 19 letters and telegrams to Denny, most of which say the same thing. A few well-chosen quotes and some judicious summary would have served the reader much better.

Nevertheless, Denny comes through as an unusual, visionary fellow, brilliant, famously obsessed with football, the game itself and its benefits to the school, and truly beloved by all.

Don Noble is host of the Alabama Public Television literary interview show “Bookmark with Don Noble.” His most recent book is Belles’ Letters 2, a collection of short fiction by Alabama women.