“For me, it was just a day of resolve and resolution, and I said ‘sign me up,” says James Stewart

“Well, the first thing I tell them is that I went to jail, and they go ‘Oooh, Grandmama,” and I say well, let me explain…” recalled Eloise Gaffney.

“It was just…you knew God was on your side,” says Washington Booker. “And we knew that it didn’t matter what we were facing. You knew if God was on your side, you’d overcome it.”

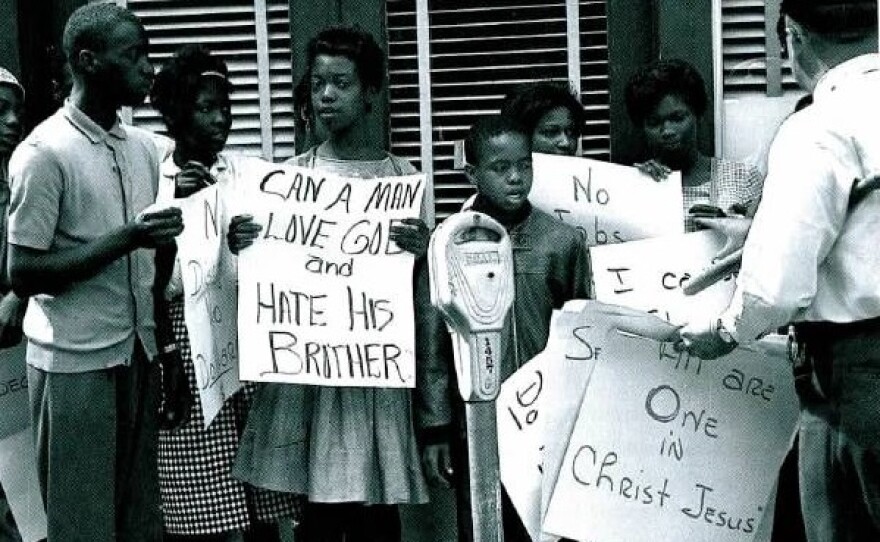

Stewart, Gaffney, and Booker are all in their early sixties. They’re all from Birmingham. They’re all African American. And fifty years ago, they made national news. On May 2, 1963, they were among the teenagers who took part in what became known as the “children’s march.” It was a protest against segregation in Birmingham. If you ever saw the film footage of Negro protesters being me with fire hoses and police dogs, that’s it. Back then, these kids were just kids. Thousands of them were inspired by civil rights leaders like the Reverend Fred Shuttles worth, James Beville, and of course Dr. Martin Luther King, Junior. But, there were other voices too. In 1963, songs by Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions were playing on local radio stations. Fats Domino and Little Willie Littlefield had hits as well. If kids in 1963 Birmingham wanted to hear this music, there was one place to go.

“I was a broadcaster,” says Shelley Stewart. “And, my audience was what I would call…a vast audience of black and white people.”

Shelley Stewart is also from Birmingham. This radio show recording you’re hearing is old. It’s from 1985. But Shelley’s career goes back even farther than that, to the late 1950’s and early 60’s. Tapes from that time are hard to find. But, the kids remember. Before the 1963 “children’s march,” Washington Booker remembers Shelley as “The Playboy.”

Now, how it got that name, I do not know,” recalled Booker. “That is probably an interesting story, but I do not know. He’d call people up like ‘baby Jones in Ensley, you up? you up? You need to get up.’ And, a few minutes Mrs. Jones will call up and say ‘Shelley, what are you doing getting people up at 5 o’clock.’ ”

“He did R and B,” says Eloise Gaffney. “But, he had…he had one saying that went ‘Timber! Let it fall!’ Something like that. And, I think that was…I know that was one of the signals.”

The school students who took part in the children’s march talk about these signals a lot.

“On the radio, Shelley made an announcement that we’re playing this song, and all of us knew that meant this was going to be a day of activity,” says James Stewart. “Even the kids who didn’t go to the meetings. We ran into them every day.”

The teenagers who took part in the 1963 children’s march see it differently They say they relied on signals and code words from Stewart’s radio show to know when the protest would begin. And even Shelley admits he knew firsthand what school kids, both black and white, could do in the race of racism. When he wasn’t on the air, Shelley the playboy played records at dance parties. That included a 1960 event at a Birmingham area hot spot called Don’s teen town About eight hundred kids there that night to witness the performance of “Shelley,” recalls Stewart.

“And the Ku Klux Klan showed up that night, and they demanded that the owner of the club, Ray Mahoney, send me out. They said they were going to kill him. The kids became very disturbed, they bolted out of the door and jumped on the Ku Klux. The Birmingham News the next day talked about a racial protest…it was no protest. Those kids, who were all white, jumped on the Ku Klux and gave me an opportunity to get away.”

That was in 1960. But, 1963 the stage was set for Shelley the Playboy and the Children’s March. Segregation in Alabama had reached a tipping point with the January inauguration of Governor George Wallace, with this phrase from his opening address…

“In the name of the greatest people who have ever trod this Earth, I draw the line in the dust, and throw down the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I saw segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever.”

“It was mean, and we lived through it,” recalled Eloise Gaffney. “And when I tell my kids, they just, they don’t….my children have a hard time believing. And for my grandchildren, it’s really far-fetched. When I say I couldn’t go to Fairpark. You had to go past by Fairpark and see the children playing, and a child asks ‘why can’t I go there?’ And, I’m sure parents then had a hard time answering questions like that.

On May 2, 1963, Gaffney would take part in the children’s march, as would James Stewart.

“My mother….when I was very young, my mother took me to town to the one of stores,” he says. “I had found out, by this time, that the tall water fountains had cold water, and the one next to it, the porcelain white basin types, had warm water. There was stool in front of the tall one, so I got up on the stool to get to the drink water, a drink of cold water, and my mother just came out of nowhere saying ‘noooo!” And, she swept me away. And at that point, she started telling me what I could and couldn’t do. And these rules were hard to comprehend. Because you had what’s wrong, what’s right, and what’s ‘white.’”

Gaffney and Stewart would be joined during the Children’s March by Washington Booker.

“I can remember seeing some kid with a banana split….some white kid sitting at the counter with this big ole banana split,” Booker recalls. “And, I mean…I don’t know. I had nothing to compare it to, how it looked. It was just a marvelous thing, and I wanted one. I wanted to sit at that counter and eat one. And, I always thought about that during the marches. When we were demonstrating, I was thinking about that. Yeah, I want to be able to sit at that lunch counter, so I can order me one of that banana splits. It seems trivial, but it was part of the way you saw the world.”

Booker, Stewart, and Gaffney would soon find themselves in the middle of the children’s march as well as the response by the Birmingham Police that would shock the nation. Birmingham area disc jockey Shelley the Playboy may have signaled the start of the children’s march in 1963, but he didn’t organize it. The credit goes to a lieutenant of Dr. Martin Luther King, the reverend James Beville. One of the teenagers he inspired was James Stewart…

“He wore one of the blue jeans suits, and had badges from everybody, and pins all over, and he was baldheaded and wore this skull cap,” Stewart remembered, “And he’s the one who was the kids’ ‘pied piper,’ he talked to us about getting involved. And we reached a point where we said ‘we need to do something to change this.’”

And that’s where Birmingham area disc jockey Shelley “the playboy” Stewart comes in. James Beville also wanted to use local radio stations to get the word out on protest day. He talked to Shelley as well as another local disc jockey named Paul White. His radio audience knew him as “Tall Paul.” Shelley says on May 2, 1963, he and “Tall Paul” announced the start of the children’s march. But, they did it in a roundabout way. They used codes.

“They had to use to get codes to get into the community. If we made an announcement ‘I want everyone to go to the park,” you don’t do that,” says Shelley. “You had to remember there were mothers and fathers who were afraid and they’d lock the door, and the teachers and principals would lock the doors. You just went around that. As they said in the old days, ‘there’s more than way to skin a cat.’ ‘Shake, Rattle, and Roll’…that’s an old tune by an artist named Joe Turner. And, we said when we played ‘Shake, Rattle, and Roll’ that’s the signal. Time to go out. So, it’s ‘Shake, Rattle, and Roll.’And, when those kids heard that, they told the teachers ‘we’re gone!’ And, the teachers tried to stop them, they were jumping out of windows at Parker High. So, that is really happened, and it escalated. Bull Connor was very upset, the local police didn’t know what to do.”

And, I mean…it was…unbelievable,” recalled Eloise Gaffney, one of the teenaged protesters. “Everybody started storming out of the school. Some got out of windows. I remember Mr. Winston stood at the door, he was the teacher everybody was afraid of, and he held his hand up and said ‘stop!’ And the kids just trampled over him, and he went back like this with his hand still in the air. They just trampled over him. So, all just marched from Parker to 16th street. Carver in north Birmingham is farther than that. But, they all marched to 16th street. That’s what they did.”

“So, we were jammed into the paddy wagons,” said James Stewart, who marched in 1963 with Gaffney. “People were running over from the park, and they had seen what was going on, and there were news people, so it was a little chaotic in the streets. And they brought out the police and arrested us. And, it was a pretty terrifying experience.” Gaffney and Stewart were both joined during the “children’s march” by Washington Booker.

“And I felt the emotions, and the crowds that lined the streets, and then when the marchers were signing and the people were singing,” says Booker. “It just went whoosh! And you felt like you were a part of it. And I had already made up my mind, I was going to jail.” “Jail was like hell,” recalled James Stewart. “It was four days of really hell.”

James Stewart of Birmingham was just a teenager on April 2, 1963. He took part in the Children’s March, and he was one of the first to arrested and jailed… “We were put in a room that could hold fifty or sixty people comfortably. They put three hundred of us in that room. It was standing room only,” Stewart recalls. “It was a concrete floor, it was concrete walls, very small windows with the bars on them. It was very hot. And they just kept putting us in that room. We had to develop a system just to sleep. We would make space on the floor, and most of us would stand around the walls, or sit in the windows. And those who slept on the floor, slept on the concrete.”

Washington Booker was in that cell too. “Going to jail didn’t slow anybody down, didn’t break anyone spirit,” Booker says. “Okay, we’re in jail, this is what we supposed to do…let’s all sing… ‘ain’t gonna let nobody turn me round, turn me round…’ And we sang. It was…it was…anything but punishment.” That was day one of the children’s march. On day two, more marches took place, more arrests were made. But when these students were put behind bars, Stewart and Booker noticed they were soaking wet.

“I was out in the park when they released the fire hoses and the police dogs,” says Eloise Gaffney, who also took part in the “children’s march.” “I was walking along, at that time it was Fifth Avenue, and it was a whole row of businesses there, and they all had glass windows, and I mean the water was so forceful it knocked me into the windows. I mean they were in the park, and the water had come over a block. Some of us found fun in it. Some of us laid on the ground and let the water push us around the park. We made a fun thing out of it. I know one of the girls who had bite marks from the dogs, so that was really scary. But the fear didn’t come. Now, when I think about it…Lord. I think it had be Lord to keep us, because we didn’t realize the danger.” The nation soon responded, including U.S. President John F. Kennedy.

“Today, as the result of responsible efforts on the part of both white and Negro leaders, over the last seventy two hours,” said Kennedy. “The business community in Birmingham has responded in a constructive and commendable fashion and pledged that substantial steps would begin to meet the justifiable needs of the Negro community. Negro leaders have announced suspension of their demonstration.”

Washington Booker saw this response this way. “Having access to jobs where we spent our money was part of what we were asking for,” he says. “We had the right be salespeople where we spent our money. But, for us as kids, that was far off. But going to the Alabama Theatre did, sitting at that lunch counter did.”

The very next year, Congress would pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which outlawed racial discrimination. Still, fifty years after the Children’s March, James Stewart is still dealing with the emotions.

"There are people who say get over it, just get over it,” he says. “When you see the size and the magnitude of what happened, it’s not easy to get over.”

Washington Booker gets those questions too, from his grandchildren. “What they can’t really get their minds around is understand how we….how we took it,” he says. “Why didn’t we fight to the death and be done with it. Maybe that’s taking to an extreme, but that’s what they wonder.”

That’s one reason these protesters are talking about it now, fifty years later. They want young people to know why they did it, and why facing the fire hoses, police dogs, and jail in 1963 was worth it.